October 2022 was a busy month for the team with two sampling trips, one at Colchester (near London), and the other at Vindolanda in northern England. Both turned out to be productive trips with nearly 400 sherds collected for organic residue analysis, which will soon be subjected to lipid extraction at the University of Bristol, and later analyzed with high resolution gas and liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry.

Colchester

For the sampling trip to Colchester we were graciously hosted by the Colchester Museum in early October. The Roman city sits below the modern city of Colchester and is still visible in the landscape. Several sites have been excavated from Colchester and the surrounding region. We focused our first phase of sampling on two sites: Sheepen Farm and Elms Farm, Heybridge.

Sheepen Farm pre-dates the Roman period as part of the site of the original Iron Age settlement of Camulodunum. It was conquered by the Romans in the Claudian invasion in 43 CE and continued until its destruction in the Boudican Revolt (61 CE).Laying outside the Roman military complex, it would have been a civilian settlement inhabited by a local British community with strong Gallic connections, as well as new people associated with the arrival of the Roman army and veteran colonists from 49 CE. The site therefore has the potential to shed light on local shifts in culinary practices in response to a newly arrived population. We focused on the early Roman period (49-61 CE), a time of increasing occupation and local industrial activities. We collected 100 sherds from Sheepen Farm. The majority of these were grog tempered jars of various sizes that may have been used as cooking pots. Grog is ground up pottery that is intentionally added to the clay to improve its firing characteristics. Additionally, nearly 10% of the sherds we collected were from terra nigra or terra rubra vessels, which originate from Northern Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium). There were even some locally made terra nigra imitations, which will keep our analyses interesting!

Heybridge also dates to the Late Iron Age and Roman periods, but it is located on the outskirts of the Colchester region. The settlement witnessed significant reorganization after the Roman invasion, including the building of a temple complex. We focused on two phases of the site: 40-70 CE and 100-130 CE. Respectively, these periods represent a transition phase and a time of growth prior to the settlement’s decline. We were able to collect 120 sherds from Heybridge, including those from bowls, dishes, jars, and mortaria. Presumably, this settlement housed a large local population that was undergoing social and economic changes associated with becoming part of the Roman world. We will use residue results to compare foodways of a site without formal military ties and more local in character (Elms Farm, Heybridge) to sites closer to the nexus of Roman imperial influence at Sheepen Farm and the Roman colonia.

Vindolanda

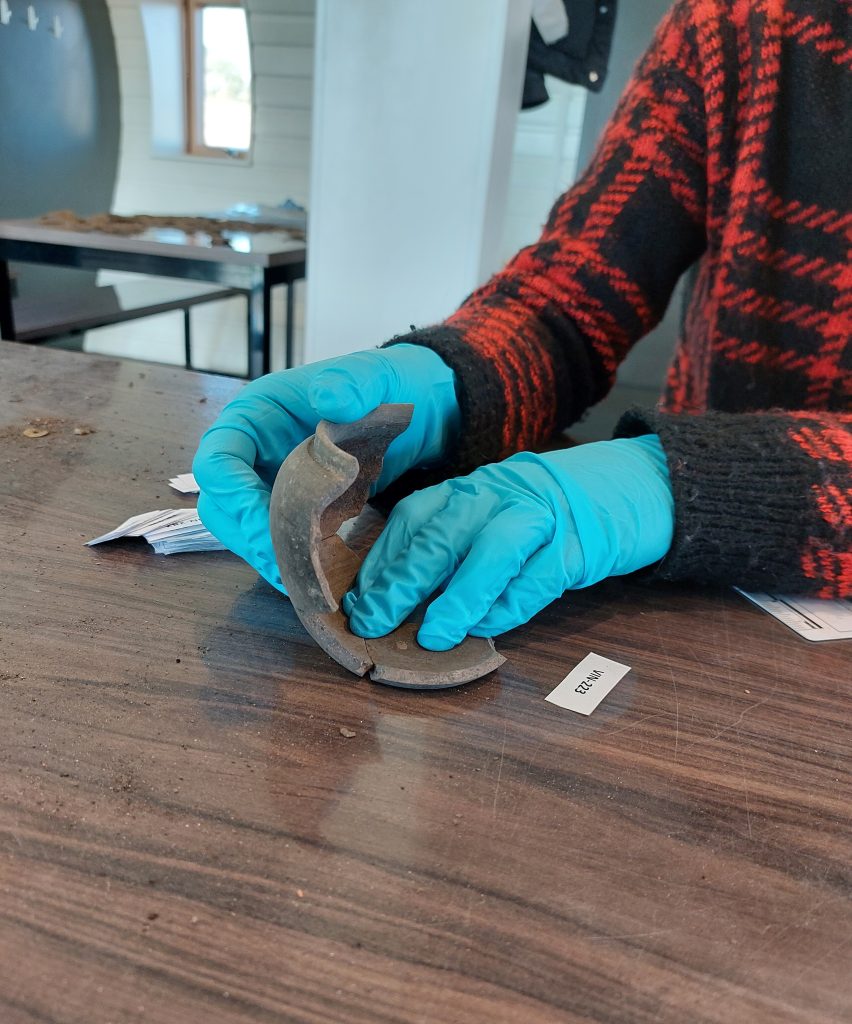

Our final sampling trip to Vindolanda was again generously hosted by the Vindolanda Trust. We were fortunate for the opportunity to spend several days directly on site, as we searched through pottery at the Robin Birley Archaeological Center. Our interest in this final sampling trip was on material from the Severan ditch, which is tightly dated to 208-212 CE. The Severan ditch and associated rampart were part of a unique, albeit short-lived fortlet built under Emperor Septimius Severus. After his military campaign against the northern tribes ended, the fortlet was torn down, the ditch filled in and built over by the third century town still present today. Visitors to the site can still see a slumping of the ground in the north where the ditch once lay below the present structures.

The Severan ditch proved to be a ripe context for sampling. We collected 157 sherds, which brings the total number of sherds from Vindolanda for residue analysis to 307. It will be interesting to see if we can extract lipids from forms we collected such as beakers and lids, which may in turn shed new light on their assumed different functions. We observed numerous specialist vessels from the Severan ditch, specifically dishes, bowls, and mortaria. We want to understand how culinary practices changed through time, as people moved into and out of the area. Like the material associated with the Vardullian (N. Spain) cavalry barracks, the Severan ditch pottery may be associated with a new group of people coming to Vindolanda from elsewhere in the Roman empire. Will culinary patterns shift at the site with longer and more intensive cultural intermingling? As we begin to analyze residue data in spring 2023, we will begin to answer these questions and hopefully shed light on Roman cross-cultural foodway adaptations.